Sogra

Susie Locklier

they tell me I have her face

the color of water that runs thru rice

the smell of onions cooking in the morning

I remember her garden, like mine

fava beans, mint leaves, fenugreek

we share the space between lines in a recipe

they tell me I have her eyes

the color of Persian turquoise

I remember her soft smile

cherry juice, torshi, dried lime

we share our sours just the same

saffron threads bloom in rose water

my fingers marked with turmeric stains

blood like pomegranate molasses

sticky full as spring

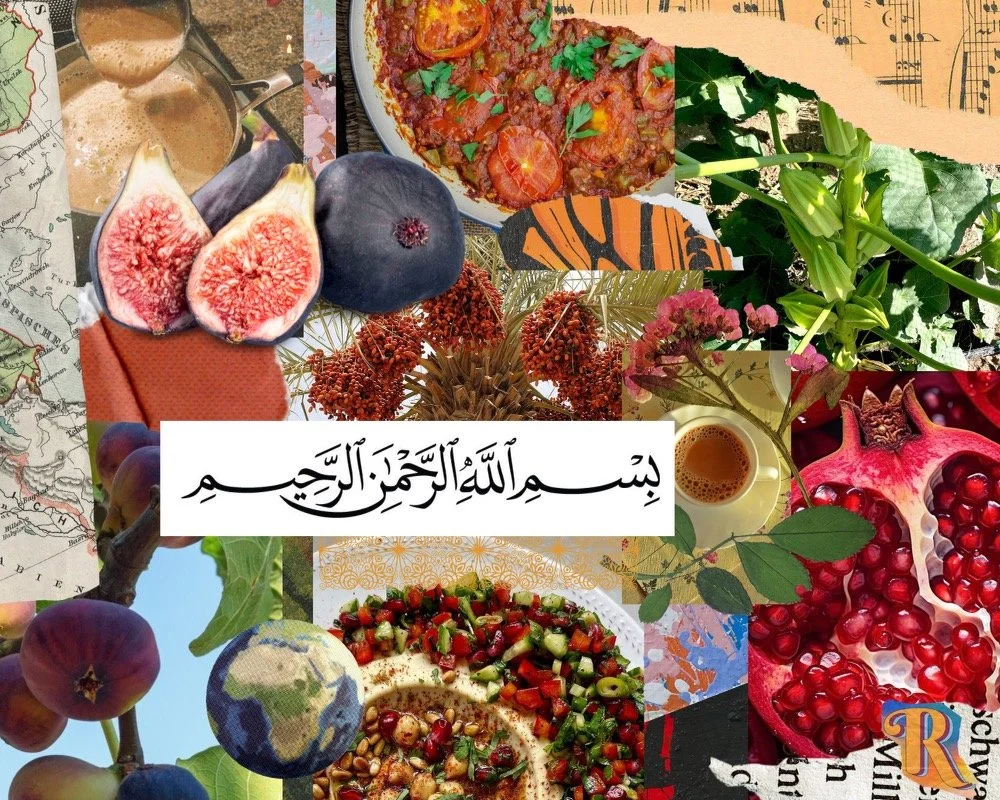

Reem Abnowf

Majlis of the Liver

An abridged menu in mourning

Words + Food: S. Maham Rizvi

Menu Design: Haitham Haddad + S. Maham Rizvi

Photos: Luca Seixas

When you come to majlis, bring your alam and a piece of your liver.

JIGAR KA TUKDA (jih-gur kaa tuk-ra) “piece of my liver”

beef liver - citrus segments - pine cone + red onion gremolata

Wear black. Spread a sheet on the floor and ground your whole being to the earth.

Hadees e Kisa begins and your heart rings…

DIL KA DARIYA (dill kaa dur-ee-yaa) “river of my heart”

seared + sliced beef heart - rose + cardamom candied beef fat

After the marsiya and the nohas have rendered you to a quiet weep or open wail, prepare for matam.

Join the room. Sway and swing in synchrony. Hit your chest in rhythm. The nohakhawan calls. You respond till you feel the reverb in your kidneys.

Ya Hussain.

GURDAH KI HAMWAR ZAMEEN (gur-dah kee hum-vaar za-meen) “leveled-earth kidney”

lamb kidney carpaccio - pickled fennel stalk - pomegranate arils - olive oil

Tabaruk, but there is no dessert served with this year’s genocide.

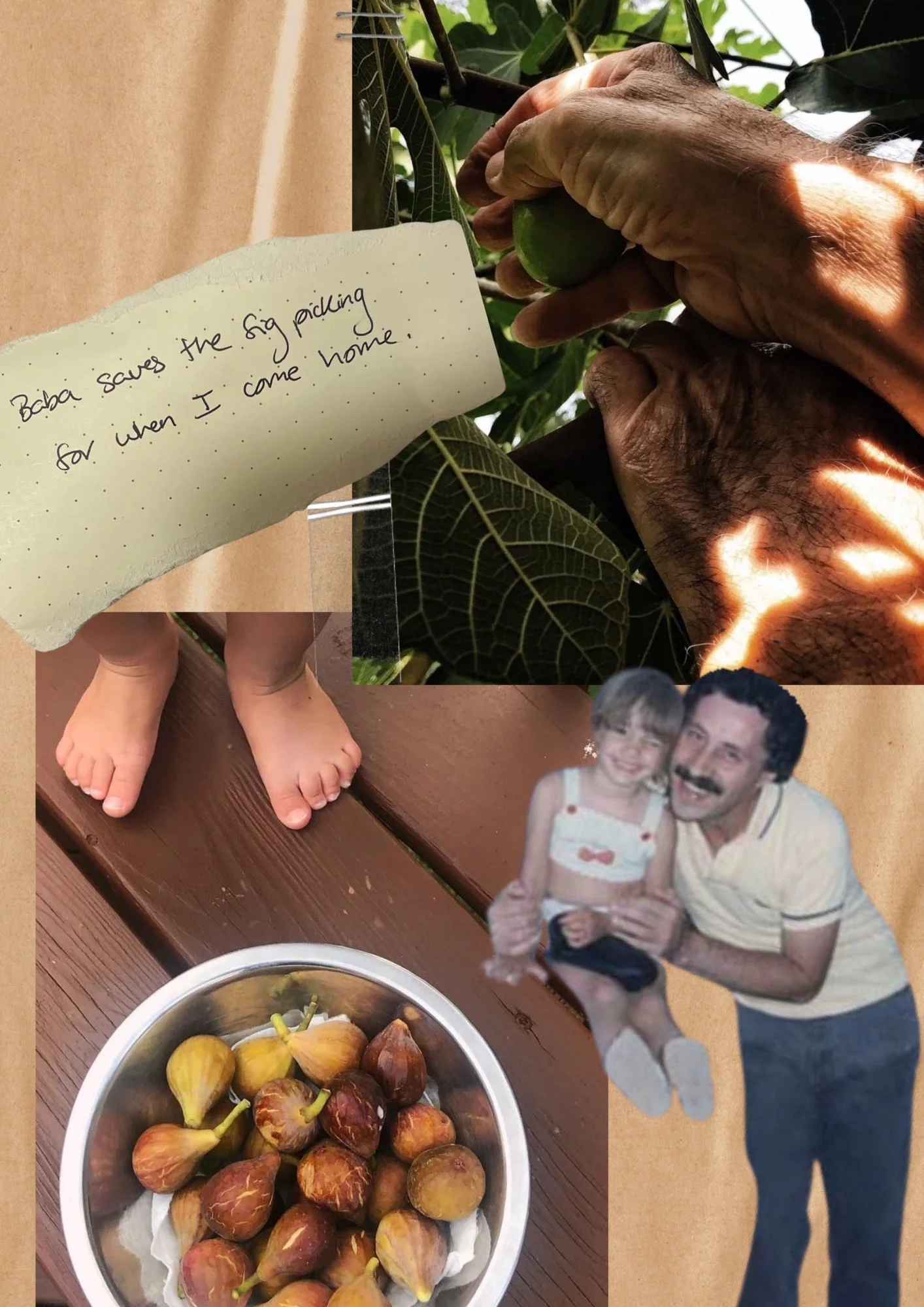

Baba saves the fig picking for when I come home // acts of inherirance

Victoria Bouloubasis

[NOTE: This poem was originally created as a performance piece between Victoria and her father, Kostantinos.

She recited the poem and he chanted Greek hymns at the intervals. It was performed in Durham, NC at EVENINGS Vol.5 on Jan. 31, 2024. It has never been published.]

Baba saves the fig picking

for when I come home.

Knuckles thick, plucking

with finesse

from the daydreams

he planted for us.

Fruit cradled in calloused palms,

bursting to say:

Eat, now that you’re here.

Eat.

Take some home.

Language fails when full.

Chanted in fragments,

more beautiful it is sung

through somber tones

as a spiritual.

<<BABA CHANTS>>

A reverence to saints and miracles and

a god who offers fig trees and roaring seas

and mountains of refuge

where the midwife needed deliverance

in a cavernous embrace.

Maybe that’s why I became her

for a two-heartbeat moment.

Maybe it was my miracle

transcending time,

hurling me into a reality that once was

ours.

Only when I became her,

to hold a crying baby against my chest

while the others panicked,

I embodied her fortitude

until the cold wind woke me from the memory.

And God told me I was there

and I am also here.

And maybe it was the most sure I have

ever been.

Because I come from

both myth and miracle and

if truth is not absolute,

neither is mine.

<<BABA CHANTS>>

Baba talks to birds in their language.

The baby on the mountain

grew to love the birds

and to sing their hymns.

I cannot sing like I used to.

He does it for me.

So I can remember what he might forget.

In the hymn, rivers of wisdom are mellifluent:

fluent in honey,

in sweetness

from where came.

Nostalgia may feed me,

but it is no reason to live.

Instead we move past the mountain,

we fly over the roaring seas

and we work work work

to plant our fig trees

on new ground.

<<BABA CHANTS>>

In his chanting

Baba declares that

the golden tongue

sings of miracles.

So we eat fruit with the birds

and we sing

our stories.

Sultan Hassan

Ek Cup Cha Da

Gurleen Parmar

For as long as I can remember, cha (tea) has been a consistent theme in my household, just as it is in most Punjabi households.

As a child, I grew up in a joint family household.

Every morning, before 5 AM, my mother would wake up to make cha for my father before he headed out for the day.

In the afternoons, my mother and chachi (dad’s brother’s wife) would ask each other, “Cha da cup bana lavaan?” (Shall I make a cup of tea?)

Soon enough, you would find them on the sofa, having their cha, chatting and gossiping, eating biscuits on the side (shout out to Parle G biscuits), and laughing as time seemed to stand still.

In the evenings, as my chacha (dad’s brother) prepared to leave for his shift and my dad returned from his morning shift, my mother or my chachi would be back in the kitchen making cha.

The act was filled with love and thought. My family’s day began and ended with a cup of cha.

A Ritual of Self-Love and Act of Service

(1 serving)

1. 1/2 cup of water

2. 1 bag of black tea

3. 1/2 spoon of Sonf (fennel)

4. 1/2 cup of milk

Place water, tea bag and sonf in a steel pot and heat until it reaches a rolling boil. Add the tea bag and snof. Once the water is boiling, add the milk. When everything is thoroughly heated, use a strainer to pour the cha into a cup. Add sugar to your liking.

Serve while hot with biscuits and love.

My best friend taught me to stir the cha occasionally once the milk is added. She learned it on her trip to India.

My chacha taught me to boil the milk separately before mixing it with the water and pathi, saying it gave the cha texture and a fuller body. His excitement in sharing this tip was evident.

My Massi and Masard Ji (mother’s sister and her husband) add their own spices—cardamom, cinnamon, clove, and nutmeg—to give it a kick. Each time you walk into their house, the overpowering aroma of cha greets you.

Every time a guest came over, they could not leave without drinking cha. They might insist they didn’t want

any, but we would make it for them, even if it was just half a cup. My mother, my chachi, and my Massi often

advised me: always make cha when someone comes over. People will say no to be polite, but it’s customary.

My people will never let anyone leave their homes on an empty stomach, and somehow cha connected us all, always serving each other in one way or another.

I remember the day my father transitioned into his next life. I arrived home from the hospital to find the house already packed with close friends and family. As I walked in, receiving hugs and condolences, my mother’s friends were in the background, standing by the stove with a huge pot brewing cha. They whispered among themselves about how much to make and how much milk would be needed for the week ahead. From that day until the day of his funeral, our house was constantly filled with people coming and going to pay their respects and offer condolences. Each new person who arrived received a cup of cha. They would sit, and soon enough they would have a cup in hand.

The beauty of my people is that they always think of everyone, even in their time of need. They put others’ needs before their own, and cha is always present in the simplest form.

Carried through many generations, it brings a sense of nostalgia for times spent with parents and ancestors. Fleeting conversations and laughter mixed with tears—somehow, cha has always found its way into these moments.

I think about the women I grew up with, the ones I love and cherish, who don’t have as much leisure or opportunity to go out with friends over brunch, but will gather at each other’s houses for a cup of cha. For them, cha is therapeutic, a way of loving themselves without saying it.

The smile on your parents’ faces or that of a distant relative when you make them a cup of cha is priceless.

Often, when I run into one of my parents’ old friends, they say, “Ginny, bahut der ho gaya teri cha peeye

hoye. Ik din aavaanga.” (Ginny, it’s been too long since I’ve had your cha. I’ll come by one day.)

Love spreads without having to say it.

My people aren’t good at saying “I love you,” “thank you,” or “I appreciate you.” They show it through acts of service.

“Aa ja, ao baith ke gallan kariye, main sade layi cha banouni haan.” (Come over, let’s sit and talk, I’ll make us some cha.)

A cup of cha has taught me the beauty and power in small acts, which can weigh so much more than words.

Bonitsa: Linking Generations and Building Connections

By Lidiana Bunda

Growing up, I stayed out of the kitchen. That’s where my mother and grandmother made my

sister and I meals that crossed cultures. We’d have everything from moussaka, sarmale, stuffed

peppers, rolata, and bonitsa to midwestern casseroles, mac and cheese, chicken nuggets, and

popcorn.

Although I loved food, I was afraid of the kitchen. I was always scared that one day it would trap

me in it like it did for the women in my family. I came to fear the kitchen and stayed away from

any cooking as I left for college and went out into the world on my own. Then, I met my husband

and admired him for his love of cooking.

The first 8 years of our relationship he did all the cooking. He knew my fears of kitchen

entrapment and respected them.

But then as I got homesick and moved to a different state, I found that food and the familiarity of

it called to me and connected me to my family. Even the simplicity of cutting up fruit and eating it

for dessert. That’s when I first ventured into the kitchen. No longer fearful of the idea of being

trapped, but now fearful of not knowing the first thing about cooking and being judged by my

family or friends, I tried cooking.

I started my kitchen experience with “vibes,” putting the ingredients I love and know together to

make something new - olive oil, rice, cheeses, potatoes, and eggplants. And before I knew it I

was creating new things, but still scared of creating the recipes from my mother and

grandmother.

Then my partner and I welcomed two new forever kids in our home from completely different

cultural backgrounds. Food then became a challenge. It became almost like two separate

languages that we spoke and didn’t quite understand each other. We tried showing them our

cuisines and making them food to make them feel welcome, but food became that cultural

barrier between us that was so hard to traverse. We tried making the foods that they told us they

were accustomed to: BBQ, steaks, fried chicken, and other southern staples. But somehow they

always reminded us that the way we made it was just “too different” and so it always went

uneaten. And I wanted to show them the love of food that my family showed me.

But I learned to share that same love in new ways, through maqluba, learned from my time

living in Palestine, or through popcorn for dinners as I had growing up in Indiana. But my

personal favorite is bonitsa. I enjoyed it as it was the thing we ate every Sunday growing up.

Bonitsa to me brought back memories of Sunday mornings at my grandmother’s kitchen table,

waiting impatiently for everyone to sit down so I could start eating the buttery cheesy and flaky

pastry. And so watching our kids fall in love with it too, even as picky eaters, brought so much

joy to my heart.

And now, although I still don’t feel comfortable cooking in the same way that I think my family

did, I have come to realize that food is pleasure and love. Food is the way that we connect to

each other and traverse generations, space, and time. Food is the way that we connect to our

past and create new and unique presents. And food is the way that we can bridge and build

relationships.

Bonitsa Recipe

40 piece box of phyllo dough - light and flaky

16oz cottage cheese

4 eggs

1 stick of butter

1 package of Bulgarian cheese

1) mix egg and cheese good together

2) melt the butter

3) brush each leaf with butter and fold in cheese mixture

4) bake 10-15 min at 370

“A Burger Restaurant in Texas”

November 17, 2023

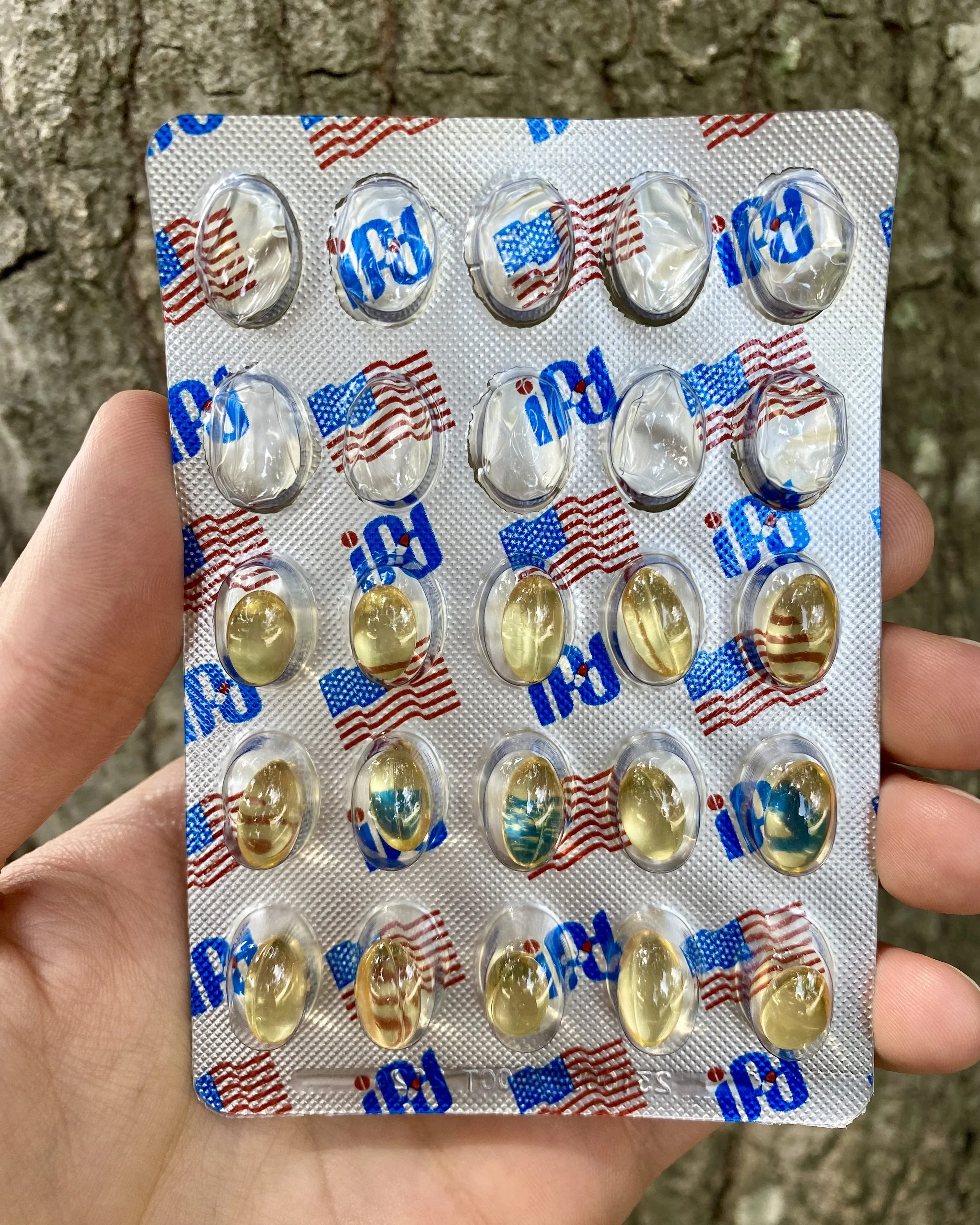

“Capsules of Garlic Oil”

June 28, 2024

“Letter to Wendy”

December 4, 2017

Edward Santos

The Best French Fries in Karachi

Aelya Salman

Some time in the late 1990s my mother sent me to the butcher across the street to get chicken. The butcher sat at the junction of several other things ideal for distracting a child, but I was good at following orders. When I saw the man with his small cart standing at the back gate of our apartment complex, however, I decided several things could happen at once so I walked over while the chicken’s neck was still draining of blood.

I found out that the man was selling French fries. I had never seen fries like his. This was exciting news, French fries at the gate. As I walked back to my building, the fresh chicken sitting warm in my arms, I decided to tell my friend Nimra.

*

Being a girl is a difficult thing. I say this having done it already for many years, and being deeply involved in the unfurling of it. Girlhood exists at the noisy, unfettered intersection of several contradictory paths that all demand you travel them.

I found it so difficult, and Nimra did not. We all knew why. Lithe, fair Nimra who knew how to navigate girlhood because everyone made it easy for her. Nimra with a very specific currency of youth. Nimra, who wouldn’t emerge from girlhood unscathed, but still better than most of us. Nimra with a knowledge of how to climb gates, which is what she suggested we do to get the fries.

We climb the gate and shout down our order, she said. I explained to Nimra that we could simply walk around the corner to place our orders but she insisted on climbing mountains (it didn’t matter that we were ten minutes from the coast and neither of us had seen anything taller than a Marriot). I was also afraid to tell her that there was no ease with which I carried my body- a perpetual project- and that even in girlhood I remained outside myself. That the only reason I would ever climb that gate would be in the hopes of being seen as someone I knew people knew I was not.

But I listened to her and one afternoon found myself walking in stride towards the gate. Within seconds Nimra hoisted herself up and looked down at me, waiting. The gate never seemed more gargantuan than it did in that moment but one by one I put down foot and then hand and then again and again till finally I emerged at the top, and watched the tight metropolitan labyrinth unfold in front of me. For the briefest of moments, I forgot my limitations. I even forgot the fries. I wondered if this is what it felt like to be her - easy and light, on top of everything. Nimra started rocking the gate to get the vendor’s attention while I politely tried not to fall.

Can we get two packets of fries?, she yelled down to the vendor. He yelled back, asking us if we wanted masala to which the answer was an obvious yes. And then we waited.

The scent of potatoes being cooked in grease filled the air, mixing with all that was around us already: raw meat, asphalt, milled cotton, paper, gasoline, dried marigolds, sea salt. As we waited it dawned on me that for all the gumption it took to climb that 10 foot gate, it would take as much to climb back down. I wondered then if it would be necessary that our friendship be a series of braveries committed by me in the pursuit of being known as someone I was not. I knew Nimra would never be brave for me, in part because she wasn’t the kind of person who thought that way, but largely because I would never ask that of anyone.

Finally, he yelled. Come get your fries.

Can’t you reach up and give them to us here? I asked, not ready to abandon my hard work.

No, came the answer. Come down to the stall or I’ll give them away. My friend leaped down the gate with all the grace of an alley cat, and made a beeline for the exit. I was immediately mad. Mad at her for not waiting. Mad at myself for not being her. Mad at my body for not being hers. Mad at myself for liking potatoes. For having told her about the fries in the first place. The indignity of being threatened was worsened by the fact that I prolonged the process by how slowly I descended the gate. It was something of a personal hell.

When we finally arrived at the stall, we were handed greasy cones made of yesterday’s news. The fries were perfect. Hot and dusted red, sturdy without being unwieldy, soft without being limp. Nimra wasn’t as taken by them as I was, but two decades later and I haven’t stopped thinking about them. Maybe she was right and they weren’t that good, and what I attributed to tastiness was just the exhaustion of hard work and low self-esteem. In that moment, though, it didn’t matter. It was early evening and all lilac sky. We ate the fries with our germy fingers, scraping dust and masala off with our teeth, tongues coated in the patina of the city.

*

I let Nimra talk me into a few more things before eventually weaning off of our friendship. I may not have had the language to articulate exactly what I felt, but I knew she was wrong for leaving me at the gate, and even wronger for disliking the fries. I didn’t care about the subjectivity of taste. If I ever did anything half as crooked as what she did to me, I would have at least pretended to like my friend’s fries. I would have let her talk to me about them for as long as she wanted. I didn’t know girlhood, maybe, but I knew that much. It was the last time I told Nimra about anything.

My family left Pakistan on the last day of June in 2001, and I didn’t think about her at all again till I found myself in my kitchen at 26, trying to replicate the same masala. I couldn’t do it.

Even independent of chicken errands, before we left the country I made it a point to say hello to the fries vendor whenever I left the complex. Always rounding the corner, of course, never from the gate.

—---

In the late 1990s my mother sent me to the butcher across the street to get chicken. When I saw the man with his small cart standing at the back gate of our apartment complex, I decided several things could happen at once.I walked over while the chicken’s neck was still draining of blood.I found out that the man was selling French fries. I had never seen fries like his. This was exciting news!. As I walked back to my building, the fresh chicken sitting warm in my arms, I decided to tell my friend Nimra.

*

Being a girl is a difficult thing. I say this having done it already for many years and being deeply involved in the unfurling of it. Girlhood exists at the noisy, unfettered intersection of several contradictory paths and you have no choice but to travel all of them. I found it difficult, but Nimra did not. We all knew why. Lithe, fair Nimra who knew how to navigate girlhood because everyone made it easy for her. Nimra with a very specific currency of youth. Nimra, who wouldn’t emerge from girlhood unscathed, but still better than most of us..

“We climb the gate and shout down our order”, she shouted I explained to Nimra that we could simply walk around the corner to place our orders, but she insisted on climbing mountains (it didn’t matter that we were ten minutes from the coast and neither of us had seen anything taller than a Marriot). I was also afraid to tell her that there was no ease with which I carried my body- a perpetual project- and that even in girlhood I remained outside myself. That the only reason I would ever climb that gate would be in the hopes of being seen as someone I knew I was not.

But I followed. . Within seconds, Nimra hoisted herself up and looked down at me, waiting. The gate never seemed more gargantuan than it did in that moment but one by one I put down foot and then hand till finally I emerged at the top, and watched the tight metropolitan labyrinth unfold in front of me. For the briefest of moments, I forgot my limitations. I even forgot the fries. I wondered if this is what it felt like to be her - easy and light, on top of everything.

“Can we get two packets of fries?”, she yelled down to the vendor. “Masala?” He yelled back=to which we answered the obvious “Yes!”.

The scent of potatoes being cooked in grease filled the air, mixing with the existing aroma- asphalt, milled cotton, paper, gasoline, dried marigolds, sea salt. As we waited it dawned on me that for all the gumption it took to climb that 10-foot gate, it would take as much to climb back down.

“Come get your fries!”.

“Can’t you reach up and give them to us here?”- I asked, not ready to abandon my hard work.

“No”, came the answer. "Come down to the stall or I’ll give them away.”

She leaped down the gate with all the grace of an alley cat, and made a beeline for the exit.

I was immediately angry.. Angry at her for not waiting. Angry at myself for not being her. Angry at my body for not being her body.. Mad at myself for liking potatoes. For having told her about the fries in the first place.

When we arrived at the stall, we were handed greasy cones made of yesterday’s news. The fries were perfect. Hot and dusted red, sturdy without being unwieldy, soft without being limp.

Nimra wasn’t as taken by them as I wasMaybe she was right, and they weren’t that good, and what I attributed to tastiness was just the exhaustion of hard work and low self-esteem. In that moment, though, it didn’t matter. By the light of the early evening lilac sky, we ate the fries with our germy fingers tongues coated in the patina of the city.

*

I let Nimra talk me into a few more things before eventually weaning off our friendship. I may not have had the language to articulate exactly what I felt, but I knew she was wrong for leaving me at the gate, and even more wrong for disliking the fries.I knew Nimra would never be brave for me, in part because she wasn’t the kind of person who thought that way, but largely because I would never ask that of anyone.

My family left Pakistan on the last day of June in 2001, and I didn’t think about her at all again until I found myself in my kitchen at 26, slicing and frying potatoes, trying to replicate the same masala. I couldn’t do it.

Chai Shai

Hiba Chohan

fields

by katie shlon

so many diaspora poets are writing

about the wet

slippery flesh of fruit and maybe

i will do that, too

in my own way.

(if i could wrap my lips around the words i would

write in that tongue too

one day.)

everyone is asking how can you be so free and

be an artist in this time?

but it’s actually so natural to be free and

on the outside, shouting

so i am asking:

how can you be so free right now

when a so called state is

rationing bags of flour and

also blowing them up and

creating the worst kind of rain

full of flour blood limbs and?

see, i am concerned about reading

every piece of news. That one had me

and

that the once 28 varieties of wheat once grew was reduced to three, imported.

fifty pound sacks only to be distributed when allowed,

how can we

write something beautiful about this?

that the land is burned at the border but it is just a “no mans land” it was once

home to

maybe 29 varieties of wheat and

our greatest songs are

written about the rain and harvest and

...شتي يا دنيي تيزيد موسمنا و يحلى

playing from the tape deck of a 1992 ford ranger...

what we picture when we sing them now!

and yet

"some people are confused about violence"

is that not

the real question?